Jean-Pierre Rampal (7 January 1922 – 20 May 2000) was a French flautist. He has been personally "credited with returning to the flute the popularity as a solo classical instrument it had not held since the 18th century."

Biography

Early years

Born in Marseille, the only child of Andrée (née Roggero) and flautist Joseph Rampal, Jean-Pierre Rampal became the first exponent of the solo flute in modern times to establish it on the international concert circuit, and to attract acclaim and large audiences comparable to those enjoyed by celebrity singers, pianists, and violinists. As it was unusual for solo flute to be featured widely in orchestral concerts, this was not easily done in the immediate years after World War II; however, Rampal's flair and presence—he was a big man to wield such a slim instrument—paved the way for the next generation of flautist superstars such as James Galway and Emmanuel Pahud.

Rampal was a player in the classical French flute tradition, although behind his superior technical facility lay the cavalier 'Latin' temperament of the Mediterranean south, rather than the more formal character of the elite north Parisian institutions. His father was taught by Hennebains, who also taught Rene le Roy and Marcel Moyse. His playing style was characterised by a bright sound, a sonorous elegance of phrasing lit up by a rich palette of subtle tone colours. He exuded a dashing, lightly articulated virtuosity that thrilled audiences in his heyday, and his natural vibrato varied according to the emotion of the music he played. Additionally, Rampal was able to breathe in the middle of extended rapid passages without losing the sweep of his rendition. His upper register and wide dynamic range were particularly notable, and the lightness and crispness of his staccato articulation (his "détaché"), heard on his early recordings, was the envy of many.

Rampal is best known for popularising the flute in the post–World War II years, recovering a vast number of flute compositions from the Baroque era, and spurring contemporary composers, such as Francis Poulenc, to create new works that have become modern standards in the flautist's repertoire.

Beginnings

Under the tutelage of his father, who was professor of flute at the Marseille Conservatoire and Principal Flute of the Marseille Symphony Orchestra, Rampal began playing the flute at the age of 12. He studied the Altès method at the Conservatoire, where he went on to win first prize in the school's annual flute competition in 1937 at age 16. This was also the year of his first public recital at the Salle Mazenod in Marseille. By then, Rampal was playing second flute alongside his father in the Orchestre des Concertes Classiques de Marseille; privately, they played duets together almost every day.

However, his remarkable career in music—which was to span more than half a century—began without the full encouragement of his parents. Rampal's mother and father encouraged him to become a doctor or surgeon, as they felt those professions were more reliable than becoming a professional musician. At the beginning of the Second World War, Rampal duly entered medical school in Marseille, studying there for three years. In 1943, authorities of the Nazi Occupation of France drafted him for forced labour in Germany. To avoid this, he fled to Paris, where it was easier to avoid detection, by frequently changing his lodgings.

While in Paris, Rampal auditioned for flute classes at the Paris Conservatoire, where he studied with Gaston Crunelle from January 1944. (Years later, he succeeded Crunelle as flute professor at the Conservatoire.) After just four months, Rampal's performance of Jolivet's Le Chant de Linos won him the coveted first prize in the conservatory's annual flute competition, an achievement that emulated that of his father Joseph in 1919.

Post-war success

In 1945, following the liberation of Paris, Rampal was invited by the composer Henri Tomasi—then conductor of the Orchestre National de France—to perform the demanding Flute Concerto by Jacques Ibert, written for Marcel Moyse in 1934, live on French National Radio. It launched his concert career overnight and was the first of many such broadcasts. In promoting the flute as a solo concert instrument at this time, Rampal acknowledged that he took his cue from Moyse. Moyse himself had enjoyed considerable popularity between the wars, although not on a truly international scale. Nevertheless, he was a role model in that he had "definitely established a tradition for the solo flute"; Moyse, Rampal said, "unlocked a door that I continued to push open."

With the war over, Rampal embarked on a series of performances: at first, within France; and then, in 1947, in Switzerland, Austria, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands. Almost from the beginning, he was accompanied by pianist and harpsichordist Robert Veyron-Lacroix, whom he had met at the Paris Conservatoire in 1946. By contrast with, as Rampal saw it, his own somewhat emotional Provençal temperament, Veyron-Lacroix was a more refined character (a "true upper class Parisian"), but each immediately found with the other a musical partnership in perfect balance. The appearance of this duo after the war has been described as a "complete novelty", allowing them to make a rapid impact on the music-going public in France and elsewhere. In March 1949, in the face of some scepticism, they hired the Salle Gaveau in Paris to perform what then seemed the radical idea of a recital programme made up solely of chamber music for flute. It was one of the first flute/piano recitals the city had seen, and caused a "sensation". The success encouraged Rampal to continue along that track. The recital was repeated the following year in Paris, and news of the young flute-player's virtuosity spread. Throughout the early 1950s, the duo made regular radio broadcasts and gave concerts within France and elsewhere in Europe. Their first international tour came in 1953: an island-hopping journey through Indonesia where ex-pat audiences received them warmly. From 1954 onwards came his first concerts in eastern Europe—most significantly in Prague, where he premiered Jindrich Feld's Flute Concerto in 1956. In the same year, he appeared in Canada—where, at the Menton festival, he played for the first time in concert with violinist Isaac Stern, who not only became a lifelong friend but also proved a considerable influence on Rampal's own approach to musical expression.

By now, Rampal had America in his sights, and on 14 February 1958 he and Veyron-Lacroix made their US debut with a recital of Poulenc, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Prokofiev in Washington, D.C. at the Library of Congress. Afterwards, Day Thorpe, music critic for the Washington Star, wrote: "Although I have heard many great flute players, the magic of Rampal still seems to be unique. In his hands, the flute is three or four music makers - dark and ominous, bright and pastoral, gay and salty, amorous and limpid. The virtuosity of the technique in rapid passages simply cannot be indicated in words." In 1959, Rampal gave his first important concert in New York City, at the Town Hall. Rampal's successful partnership with Veyron-Lacroix produced many award-winning recordings, notably their 1962 double LP of the complete Bach flute sonatas. They performed and toured together for some 35 years, until the early 1980s, when Veyron-Lacroix was forced to retire owing to ill-health. Rampal then formed a new and also long-running musical partnership with American pianist John Steele Ritter.

Even as he pursued his career as a soloist, Rampal remained a dedicated ensemble player throughout his life. In 1946, he and oboist Pierre Pierlot founded the Quintette a Vent Francais (French Wind Quintet), formed of a group of musical friends who had made their way through the war: Rampal, Pierlot, clarinettist Jacques Lancelot, bassoonist Paul Hongne, and horn-player Gilbert Coursier. Early in 1944 they had played together, broadcasting at night from a secret "cave" radio station at the Club d’essai in rue de Bec, Paris—a programme of music outlawed by the Nazis, including works with Jewish links by composers such as Hindemith, Schoenberg and Milhaud. The Quintet remained active until the 1960s.

Between 1955 and 1962, Rampal took up the post of Principal Flute at the Paris Opera, traditionally the most prestigious orchestral position open to a French flautist. Having been married in 1947 and now a father of two, the post offered him a regular income to offset the vagaries of the freelance life, even though his solo career as a recording artist was developing rapidly. That career was to take him away from the Paris Opera House for extended periods during his tenure there.

Recovering the Baroque

Rampal's first commercial recording, made in 1946 for the Boite a Musique label in Montparnasse, Paris, was of Mozart's Flute Quartet in D, with the Trio Pasquier. Among composers, Mozart was to remain his principal love ("Mozart, it is true, is a god for me", he said in his autobiography), but Mozart by no means formed the cornerstone of Rampal's works. A key element in Rampal's success in the years immediately after World War II—aside from his evident ability—was his passion for the music of the Baroque era. Aside from a few works by Bach and Vivaldi, Baroque music was still largely unrecognised when Rampal started out. He was well aware that his determination to promote the flute as a prominent solo instrument required a wide and flexible repertoire to support the endeavour. Accordingly, he seems to have been clear in his own mind from the beginning about the importance, as a ready-made resource, of the so-called "Golden Age of the Flute", as the Baroque era had become known. Hundreds of concertos and chamber works written for the flute in the 18th century had fallen into obscurity, and he recognised that the sheer abundance of this early material might offer long-term possibilities for an aspiring soloist.

However, Rampal was not the first flute player to have taken an interest in the Baroque. The catalogue of flute music recorded on 78 rpm discs reveals that there was some prior taste for the music of Vivaldi, Telemann, Handel, Pergolesi, Scarlatti, Leclair, Loeillet, and others. Claude-Paul Taffanel, widely held to be the father of the French Flute School, had a liking for the music of the Baroque and was the first to revive interest in the flute sonatas of J.S. Bach and the flute concertos of Mozart. Taffanel's pupil Louis Fleury continued this interest through his Société des Concerts d’Autrefois and his performances with the Société Moderne des Instruments à Vent, and he also supervised the publication of a number of scores. Marcel Moyse, who took the flute to a new level of popularity between the First and Second World Wars, recorded pieces by Telemann, Schultze, and Couperin; of Bach's work, he recorded the Brandenburg concertos, the Suite No. 2 in B Minor for flute and orchestra, and the Trio Sonata for Flute, Violin, and Bass. Likewise, Rene le Roy, an equally celebrated soloist in Europe and America during the 1930s and 1940s, achieved success with performances of Baroque sonatas, and also made interpreting Bach's Partita in A minor for unaccompanied flute a personal speciality after the piece was rediscovered in 1917.

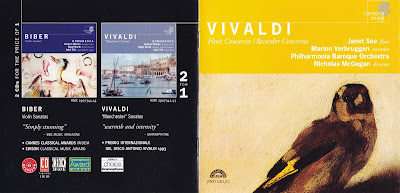

Rampal pursued his passion for the Baroque repertoire systematically and with extraordinary enthusiasm. Even before World War II, he had begun collecting obscure sheet music from the Baroque—making himself familiar with original publishers and catalogues, even though very few published editions were then available. He went on to research in libraries and archives in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Turin, and every other major city he performed in, and corresponded with others across the musical world. From original sources, he developed a detailed understanding of the Baroque style. He studied Quantz and his famous treatise On Playing The Flute (1752), and later acquired an original copy of it. For Rampal, the Baroque legacy was fuel to set alight a renewed interest in the flute, and it was his energy in pursuing this goal that set him apart from his forbears. Whereas Le Roy, Laurent and Barrère had all recorded two or three of Bach's flute sonatas between 1929 and 1939, between 1947 and 1950 Rampal recorded all of them for Boîte à Musique, and was beginning to regularly perform the complete Bach sonatas in recital, organising them across two evenings. Also, as early as 1950-51 he became the first to record all six of Vivaldi's Op.10 concertos, an exercise he was to repeat several times in later years.

Rampal had sensed that the time was right. In an interview with the New York Times, he offered one explanation for the appeal of Baroque music after the war: "With all this bad mess we had in Europe during the war, people were looking for something quieter, more structured, more well balanced than Romantic music." In the process of excavating forgotten works for performance, Rampal also had to discover new ways of playing that era's music. He applied his own bright tone and the liveliness and freedom of his style to the original texts, developing along the way a very individual approach to interpretation and, after the Baroque style, to improvised ornamentation. Throughout, Rampal was never tempted to perform on a period instrument; the movement that championed "authentic" instruments for "true" performance of Baroque music had not yet emerged. Instead, he drew on the full range of effects offered by the modern flute to reveal fresh elegance and nuance to Baroque compositions. It was this modernity–the richness and clarity of his sound and the freedom and personality in his expression–combined with a sense of hidden treasures being shared that caught the attention of a wider musical public. "Enchantment is the best possible word to describe this concert", said one Canadian reviewer for Le Devoir in 1956; "Rampal's playing struck me through its variety, its flexibility, its colour and above all its liveliness." This striking effect can be heard on his earliest recordings, between 1946 and 1950. During this period, Rampal quickly benefited from the birth of the long-playing gramophone record. Before 1950, all of his recordings were on 78 rpm discs. After 1950, the 33⅓ rpm long-playing era allowed much greater freedom to accommodate the rate at which he was committing performances to record. At the same time, the birth of the television age ensured Rampal a wider prominence in France than any previous flute-player, through his many concert and recital appearances in the late 1950s and beyond.

Thus, even in the first 15 years after the war, Rampal covered a huge amount of ground in this enterprise, and the post-war rediscovery of the Baroque became inseparable from Rampal's own developing solo career. A great deal of the material Rampal performed and recorded he also published, supervising sheet music collections in both Europe and the US. In his autobiography, he remarked that he had felt it part of his "duty" to expand as much as possible the repertoire for fellow flautists as well as for himself. In trying to keep the flute before the musical public in the widest sense possible, Rampal also played in as many groups and combinations as he could, a habit he continued for the rest of his life.

In 1952 he founded the Ensemble Baroque de Paris, featuring Rampal himself, Veyron-Lacroix, Pierlot, Hongne, and violinist Robert Gendre. Remaining together over almost three decades, the ensemble proved one of the first musical groups to bring to light the chamber repertoire of the 18th century.

Collaborations

Through his recordings for labels including L'Oiseau-Lyre and, from the mid-1950s, Erato, Rampal continued to give new currency to many "lost" concertos by Italian composers such as Tartini, Cimarosa, Sammartini, and Pergolesi (often collaborating with Claudio Scimone and I Solisti Veneti), and French composers including Devienne, Leclair, and Loeillet, as well as other works from the Potsdam court of the flute-playing king Frederick the Great. His 1955 collaboration in Prague with Czech flautist, composer, and conductor Milan Munclinger resulted in an award-winning recording of flute concertos by Benda and Richter. In 1956, with Louis Froment, he recorded concertos in A minor and G major by C.P.E. Bach. Other composers of the era, such as Haydn, Handel, Stamitz, and Quantz, also figured significantly in his repertoire. He was open to experimentation; once, through laborious over-dubbing, he played all five parts in an early recording of a flute quintet by Boismortier. Rampal was the first flautist to record most, if not all, of the flute works by Bach, Handel, Telemann, Vivaldi, and other composers who now comprise the core repertoire for flute players.

Despite his commitment to the Baroque, Rampal extended his researches into the Classical and Romantic eras in order to establish some continuity to the repertoire of his instrument. For example, his first "recital" LP, released in both America and Europe, featured music from Bach, Beethoven, Hindemith, Honegger, and Dukas. Aside from recording familiar composers such as Mozart, Schumann, and Schubert, Rampal also helped bring the works of composers such as Reinecke, Gianella, and Mercadante back into view. Additionally, while the Baroque had provided the platform for his revival of the flute, Rampal was well aware that the health of its continuing appeal depended on him and others displaying the whole range of the repertoire. From the start, his recital programmes included modern compositions as well. Rampal gave the first Western performance of Prokofiev's Sonata for Flute and Piano in D, which in the 1940s was in danger of being co-opted for the violin, but which has since become established as a flute favourite. Over his career, he performed all of the flute masterpieces that were composed in the first half of the 20th century, including works by Debussy, Ravel, Roussel, Ibert, Milhaud, Martinů, Hindemith, Honegger, Dukas, Françaix, Damase, Kuhlau, and Feld.

By the early 1960s, Rampal was established as the first truly international modern flute virtuoso, and was performing with many of the world's leading orchestras. Just before his first recital tour of Australia in 1966, a leading newspaper said: "he is to the flute what Rubinstein is to the piano and Oistrakh to the violin". Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Rampal's publicity in America continued to hail his celebrity; one newspaper hailed him as "the prince of flute-players".

As a chamber musician, he continued to collaborate with numerous other soloists, forming particularly close and long-lasting collaborations with violinist Isaac Stern and cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. A number of composers wrote especially for Rampal, including Henri Tomasi (Sonatine pour flûte seule, 1949), Jean Françaix (Divertimento, 1953), Andre Jolivet (Concerto, 1949), Jindřich Feld (Sonata, 1957), and Jean Martinon (Sonatine). Others included Jean Rivier, Antoine Tisne, Serge Nigg, Charles Chaynes, and Maurice Ohana. In addition, he premiered a large number of works by contemporary composers such as Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, Ezra Laderman, David Diamond, and Krzysztof Penderecki. His transcribing in 1968, at the composer's own suggestion, of Aram Khatchaturian's Violin Concerto (recorded 1970) showed Rampal's willingness to broaden the flute repertoire further by borrowing from other instruments. In 1978, the Armenian-American composer Alan Hovhaness wrote his Symphony No. 36, which contained a melodic flute part tailored especially for Rampal, who gave the premiere performance of the work in concert with the National Symphony Orchestra.

The only piece dedicated to Rampal that he never publicly performed was the Sonatine (1946) by Pierre Boulez, which—with its spiky, explosive figures and extravagant use of flutter-tonguing—he found too abstract for his taste. Elsewhere, when sometimes criticised for not playing enough contemporary avant-garde work—"Avant garde of what?" he would ask —Rampal confirmed his aversion to music that looked "like the blueprints for a plumber... pieces that go tweak, twonk, thump, snort—this doesn't inspire me."

One piece in particular, written with Rampal in mind, has since become a modern standard in the essential flute repertoire. Rampal's compatriot Francis Poulenc was commissioned by the Coolidge Foundation of America in 1957 to write a new flute piece. The composer consulted with Rampal regularly on shaping the flute part, and the result, in Rampal's own words, is "a pearl of the flute literature". The official world premiere of Poulenc's Sonata for Flute and Piano was performed on 17 June 1957 by Rampal, accompanied by the composer, at the Strasbourg Festival. Unofficially, however, they had performed it a day or two earlier to a distinguished audience of one: the pianist Artur Rubinstein, a friend of Poulenc's, was unable to stay in Strasbourg for the evening of the concert itself, and so the duo obliged him with a private performance. Poulenc was then unable to travel to Washington for the US premiere on 14 February 1958, so Veyron-Lacroix took his place, and the sonata became a key offering in Rampal's US recital debut, helping launch his long-lived trans-Atlantic career.

L'homme à la flûte d'or

As the owner of the only solid gold flute (No. 1375) made, in 1869, by the great French craftsman Louis Lot, Rampal was the first internationally renowned "Man With the Golden Flute". Rumours of the survival of the 18-carat gold Lot had been circulating in France for years before the Second World War, but no one knew where the piece had gone. In 1948, almost by chance, Rampal acquired the instrument from an antiques dealer who had wanted to melt the instrument down for the gold—evidently unaware that he was in possession of the flute equivalent of a Stradivarius. With family help, Rampal raised enough funds to rescue the precious instrument, and went on to perform and record with it for 11 years. In interviews, Rampal said he thought the gold—by contrast with silver—made his naturally bright, sparkling sound "a little darker; the colour is a little warmer, I like it". Only in 1958, when presented during his debut US tour with a 14-carat gold instrument made after the Lot pattern by the William S. Haynes Flute Company of Boston, did Rampal stop using the 1869 original. After one final recording in London, he consigned the golden Lot to the safety of a bank vault in France, and thereafter made the Haynes his concert instrument of choice.

Celebrity

Throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, Rampal remained especially popular in the US and Japan (where he had first toured in 1964). He toured America annually, performing at every leading venue—from Carnegie Hall and Avery Fisher Hall to the Hollywood Bowl —and was a regular presence at the Mostly Mozart Festival at the Lincoln Center in New York. At his busiest, he performed between 150 and 200 concerts a year.

His range extended well beyond the orthodox: alongside the outpouring of classical recordings, he recorded Catalan and Scottish folk songs, Indian Music with sitarist Ravi Shankar, and, accompanied by the distinguished French harpist Lily Laskine, an album of Japanese folk melodies that was named album of the year in Japan, where he became adored by a new generation of budding flute-players. He also recorded Scott Joplin rags and Gershwin, and collaborated with French jazz pianist Claude Bolling. The Suite for Flute and Jazz Piano (1975), written by Bolling especially for Rampal, went to the top of the US Billboard charts and remained there for ten years. This raised his profile with the American public even further and led, in January 1981, to a TV appearance on Jim Henson's The Muppet Show, where he played "Lo, Hear the Gentle Lark" with Miss Piggy—and, suitably attired, "Ease on Down the Road" in a scene loosely based on the folktale of the Pied Piper.

Back on the classical stage, he was not afraid to be, as he put it, "a bit of a ham"; when performing Scott Joplin's Ragtime Dance and Stomp as a concert hall encore, for example, he provided extra percussion by stamping his feet rhythmically on stage in time to the music. Meanwhile, Bolling and Rampal came together again for Bolling's Picnic Suite (1980) with guitarist Alexander Lagoya, the Suite No. 2 for Flute and Jazz Piano (1987), and also to perform the instrumental theme song "Goodbye For Now" by Stephen Sondheim for Reds, Warren Beatty's Oscar-winning 1981 movie about the Communist revolution in Russia. His reputation as a celebrity soloist in America became such that, as Esquire reported, one critic dubbed him "the Alexander of the flute, with no new worlds to conquer." Following a performance of Mozart's Concerto for Flute, Harp, and Orchestra with the New York Philharmonic in 1976, New York Times critic Harold C. Schonberg wrote "Mr. Rampal, with his effortless long line, his sweet and pure tone and his sensitive musicianship, is of course one of the great flutists in history." Throughout these years of mounting celebrity, Rampal continued to research and edit sheet-music editions of flute works for publishing houses including Georges Billaudot in Paris and the International Music Company in the US.

Achievement

Of the primal appeal of the flute, Rampal once told the Chicago Tribune: "For me, the flute is really the sound of humanity, the sound of man flowing, completely free from his body almost without an intermediary[...] Playing the flute is not as direct as singing, but it's nearly the same." Through him, the full range of expressive powers of which the flute was capable were convincingly displayed to a wider public.

Calling Rampal "an indisputably major artist", the New York Times said "Rampal's popularity was grounded in qualities that won him consistent praise from critics and musicians in the first decades of his career: solid musicianship, technical command, uncanny breath control, and a distinctive tone that eschewed Romantic richness and warm vibrato in favor of clarity, radiance, focus and a wide palette of colorings. Younger flutists assiduously studied and tried to copy his approaches to tonguing, fingering, embouchure (the position of the lips on the mouthpiece) and breathing."

Rampal remained unapologetic about his use of modern instruments, often wondering aloud whether Bach or Mozart would have tolerated the Baroque instrument ("little more than an awkward pipe") if they'd had its more perfectly tuned and better constructed modern equivalent at their disposal. In answer to the conundrum of Mozart's well-known remark that he couldn't bear the flute, for example, Rampal once said in an interview: "I don't think that statement by Mozart is to be taken too seriously. At the time he wrote it, Mozart had troubles with love and with money. His patron wasn't satisfied with the composer's first try and almost threw the composition back in Mozart's face. Remember, Mozart always wrote on commission, and at the time the flute was one of the instruments that most bad amateurs could play just a little. Mozart didn't detest the flute, he detested bad flautists."

Aside from his own recorded legacy, it was as much through his inspiration of other musicians that Rampal's contribution can be appreciated. Throughout the busiest years of his concert career, Rampal continued to find time to teach others, encouraging his students to listen not only to other flute players, but also to take inspiration from other great musical interpreters—be they pianists, violinists, or singers. He maintained a clear opinion about the right balance between "virtuosity" and aspiring to real musical expressiveness. "Of course", he said, "you have to master all the problems of technique to be free to express yourself through your instrument. You can have a big imagination and a big heart but you cannot express it without technique. But the first quality you must have to be good, to be inspiring, is the sound. Without the sound you cannot achieve anything. The tone, the sound, the sonorité is most important. Otherwise, with the fingers alone it is not enough... everyone these days has the fingers, the virtuosity... but the sound, the tone, that's not so easy."

Following the foundation of the Nice Summer Academy in 1959, Rampal held classes there annually until 1977. In 1969 he succeeded Gaston Crunelle as flute professor at the Paris Conservatoire, a position he held until 1981. When 21-year-old James Galway sought Rampal out in Paris in the early 1960s, Galway felt that he was going to meet "the master". As Galway says in his own autobiography, "For me, of course, it was simply a sensation to meet this great musician; like a fiddler meeting Heifetz." Rampal took Galway along to the Paris Opera to watch him play, and, said Galway, inspired him rather than taught him on the occasions they were together. William Bennett, too, has commented on Rampal's infectious enthusiasm for music-making: "his repute came more from his musical sparkle and the happy personality which radiated to the audience". Bennett had also sought Rampal out for lessons in Paris and was "instantly delighted with him—his humour, and his generosity—especially for his sharing my enthusiasm for other great players such as Moyse, Dufrene & Crunelle".

Rampal's principal American students include concert and recording artist Robert Stallman and Ransom Wilson, who has followed in his mentor's footsteps as conductor as well as flautist. Wilson said: "Rampal's greatest gift was his very spirit. Yes, he was one of the greatest flutists in history, but that achievement paled in comparison to his infectious joie de vivre. He had such musical passion that every audience member felt they were being given a private concert. He was magic!"

Family life

Rampal and his harpist wife Françoise, née Bacqueryrisse, were married on 7 June 1947. They made their home in Paris, living in the appropriately named Avenue Mozart. They have two children, Isabelle and Jean-Jacques. Each year they holidayed at their house on Corsica, where Jean-Pierre was able to indulge his passion for boating, fishing and photography. Well-known for his love of good food, he liked to maintain a private rule wherever he went on tour that he would eat "only the cuisine of the country" he was in, and he looked forward to his post-concert dinners with relish. He developed a particular fondness for Japanese cuisine, and in 1981 wrote an introduction to The Book of Sushi written by a chef and a master sushi teacher. Rampal's autobiography Music, My Love appeared in 1989 (published by Random House).

Leaving the stage

In later years, Rampal took up the conductor's baton with more frequency, but he continued to play well into his late 70s. The last work of importance dedicated to him was Krzysztof Penderecki's Flute Concerto, which he premiered in Switzerland in 1992, followed by its first performance in America at the Lincoln Centre. Rampal's last public recital was held at the Theatres des Champs-Élysées in Paris in March 1998, when he was 76; he performed works by Mozart, Beethoven, Czerny, Poulenc, and Franck. His last recording was made with the Pasquier Trio and flautist Claudi Arimany (trio and quartets by Mozart and Hoffmeister) in Paris in December 1999.

After Rampal died in Paris of heart failure in May 2000 at age 78, French President Jacques Chirac led the tributes, saying "his flute spoke to the heart. A light in the musical world has just flickered out." Isaac Stern, who had collaborated extensively with Rampal, recalled: "Working with him was pure pleasure, sheer joy, exuberance. He was one of the great musicians of our time, who really changed the world's perception of the flute as a solo instrument." Flautist Eugenia Zukerman observed: "He played with such a rich palette of color in a way that few people had done before and no one since. He had an ability to imbue sound with texture and clarity and emotional content. He was a dazzling virtuoso, but more than anything he was a supreme poet." The trustees and staff of Carnegie Hall in New York, where Rampal had performed 45 times over a 29-year period, hailed him as "one of the greatest flutists of the 20th Century and one of the greatest musical spirits of our time." The obituary in Le Monde claimed him to be no less than "L'inventeur de la flute" and celebrated all the musical characteristics that charmed audiences worldwide: "la sonorite sublime, la vivacite des phrases, la virtuosite laissaient une impression de bonheur, de joie a ses auditeurs".

James Galway, Rampal's globally known successor as "The Man with the Golden Flute", dedicated performances to him and recalled elsewhere how as a teenager he had been captivated by the sound of Rampal's "fluid technique" and "the beauty of his tone". For a young musician in the 1960s, he said, listening to Rampal's recordings "was a step into the stars as far as flute playing was concerned." He recalled also the generous encouragement Rampal gave him following their meetings in Paris. Of the passing of his "hero", Galway added: "He was the first major influence in my life and I am still grateful for everything he ever did for me. He was a great influence on the flute world and the musical world in general, bringing to ordinary folk through his music making a charm which enhanced their everyday lives."

At Rampal's funeral, fellow flautists played the Adagio from Boismortier's Second Flute Concerto in A Minor in recognition of his lifelong passion for Baroque music in general and Boismortier in particular.

Jean-Pierre Rampal is buried in the Cimetière du Montparnasse, Paris.

Honours

During his lifetime, Rampal had many honours bestowed upon him. His several Grand Prix du Disque from l'Académie Charles Cros included awards for his recording of Vivaldi's Op. 10 flute concertos (1954), his recording of concertos by Benda and Richter (1955) with the Chamber Orchestra of Prague (Milan Munclinger), and in 1976 the Grand Prix ad honorem du Président de la République for his overall recording career to date. He also received the "Réalité" Oscar du Premier Virtuose Francais (1964), the Edison Prize; the Prix Mondial du Disque; the 1978 Leonie Sonning Prize (Denmark), the 1980 Prix d’Honneur of the 13th Montreux World Recording Prize for all his recordings; and the Lotos Club Medal of Merit for his lifetime's achievement. In 1988, he was created President d’honneur of the French Flute Association "La Traversière", while in 1991 the National Flute Association of America gave him its inaugural Lifetime Achievement award.

State honours included being made Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur (1966) and Officier de la Légion d’Honneur (1979). He was also made a Commandeur de l’Ordre National du Mérite (1982) and Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et Lettres (1989). The City of Paris presented him with the Grande Médaille de la Ville Paris (1987), and in 1994 he received the Trophée des Arts from the Franco-American French Institute Alliance Française "for bridging French and American Cultures through his magnificent music". In 1994 the Ambassador of Japan presented Rampal with the Order du Tréasor Sacre, the highest distinction presented by the Japanese government, in recognition of having inspired a new generation of aspiring flute-players in that country. Strangely, with his enduring international fame assured, Rampal himself came to feel in later years that his own reputation within his native France had in some way diminished. It was "curious", he wrote in Le Monde in 1990, that no French music critics appeared to take any notice of his latest recordings: "Everything continues as if I didn't exist", he said; "This doesn't matter; I still play to full houses." But after his death, there was no shortage of public accolades to reflect the fact that he was indeed a source of national pride.

The Jean-Pierre Rampal Flute Competition, begun in his honour in 1980 and open to flautists of all nationalities born after 8 November 1971, is held tri-annually as part of the Concours internationaux de la Ville de Paris.

In June 2005, the Association Jean-Pierre Rampal was founded in France to perpetuate the study and appreciation of Rampal's contribution to the art of flute-playing. Among other projects, which include maintaining the Jean-Pierre Rampal Archive, the Association has collaborated in the re-release on the Premier Horizons label of a number of early Rampal performances on CD.

Marian

Marian